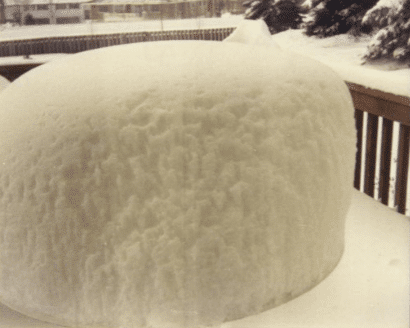

This photo was what the deck of my childhood home in Bloomington, MN looked like the morning after the great Halloween Blizzard of 1991! It was certainly an Unexpected Experience even for Minnesota natives. While we have had snow as early as September, getting 31 inches on Halloween is inconsistent with even Minnesota’s wacky weather. So, what does this talk of snow and inconsistency have to do with communication?

In this series, we’ve talked a lot about the importance of the ED, shared stories that demonstrate what’s most important to patients and families, and highlighted the foundational aspect of empathy. Last time we turned to the “what to do” best practices for communication, discussing strengths that our DTA team has seen when coaching physicians, PAs, techs, NPs, coordinators, EMTs, and medics from Emergency Departments across the country.

This time we’ll turn to some of the inconsistencies that we often encounter. At DTA when coaching, we consider an “inconsistency” as a practice or behavior that we see the care team member do some of the time but we’d like to see it done more often. These inconsistencies usually build off a strength and are just the next level of refinement with that skill.

Let’s look at some of the top inconsistencies that we’ve coached with staff in the ED:

Use names (yours, theirs, others): Patients are faced with a multitude of people going in and out of their room on a given day. Intentionally stating your role and reason for being in the patient’s room demonstrates courtesy and respect. Just like introducing yourself personalizes the care, referring to patients by their name throughout the various encounters furthers this connection.

Introductions and personalization of care by using names builds off the strength of showing courtesy and respect that we highlighted last time. We find that often staff do a nice job of introducing themselves and using the patient’s name the first time they enter the room, however, after that many revert to just knocking and entering or saying “It’s me again.” Additionally, many will refer to “your nurse” or “the doctor” but personalizing this further by adding in names really helps!

Make a social connection- This goes hand-in-hand with the strength of humor that we touched on last time. Not every situation is an appropriate one in which to infuse humor but an extension of that skill is finding a way to make a social, non-clinical connection. Basically, this involves finding a way to talk to a patient and let them know that you see them as a person. Use cues in the room such as commenting on what’s on TV or an article of clothing: “How are the Vikings doing?” These can be easy ways to make an important connection with a patient.

Ask permission – This is one of the most subtle and picky things that I find myself coaching and yet it is one of the most powerful. Patients are often scared and in a new situation where they may feel like so many things are out of their control. One of the best things that caregivers can do is to orient the conversation such that patient choice is maximized. A simple way to do this (and one that shows a ton of courtesy and respect) is to ask for a patient’s permission before just going ahead and doing things to them.

Asking permission builds off the strength of narrating your care that we reviewed last time. If someone is not comfortable talking while they’re working, I’ll coach them to narrate their care. But, if they are already strong in that, the next level I’ll suggest is a subtle nuance in the language that they use to narrate their care. Instead of “I’m going to check your blood pressure” (good narration of care), you can add in the skill of asking permission : “Would it be okay if I checked your blood pressure? Which arm would you prefer?”

Discuss Duration – This skill builds off the strengths of explanations and reviewing the plan. Often people do a good job of reviewing the plan before they leave the room but they may not be attaching some timeframes to their review. Often we’ll hear things like “We’ll get some labs done and have a CT and then I’ll be back in to discuss the plan.” In those situations, I think the provider has done a good job of reviewing the plan before leaving the room, but I would encourage them to add in some timeframes to this. “The blood work that we’re running will take about 45 minutes after they draw it from you here in the room. And the CT itself will only take about 5 to 10 minutes, however, it will be about another 45 after that until I will be able to see the images.” We spent quite a bit of time talking about this skill in a previous blog post if you’d like to read more.

Thank – Very simply this involves fostering an attitude of gratitude! This is a great way to close any encounter and it lets patients know you appreciate caring for them. You can do this by sincerely thanking the patient or family member for their time and cooperation, or thanking them for being patient. Often, patients will beat the staff to the thanking and in those cases, many will do the polite thing and say “You’re welcome.” I’ve also seen plenty of staff flip this around and thank them (the patient) before leaving.

This builds off the strengths we discussed of knocking and showing courtesy and respect when entering the room. Caregivers may have a strong/warm welcome as they enter the room but many simply rush out at the end without a warm exit or close to the encounter. Often we find that staff will thank one another consistently, they just don’t do that as often with their patients.

Wash hands before entering –Not only is this a patient safety and infection control concern, it communicates to the patient that we are putting their health first. The best practice for those using the foam hand sanitizer is to keep foaming as you walk into the room. This provides a visual cue to the patient that you have cleansed your hands before entering and you value their safety. Additionally, patients say that their perception of the cleanliness of the environment is tied to seeing everyone washing their hands.

This falls under the “inconsistency” category because it’s often the case that staff washes their hands the first time in the room or when they know that they are going in to provide direct, hands on care, but they don’t remember to wash/foam as much when they are just going back in the room to check on a patient or don’t intend to touch them. The reality is that patients don’t know that you’re just popping in and not intending to provide direct care.

These are some of the most frequent inconsistencies that we’ve seen in the Emergency Department staff we’ve coached. Hopefully you can see how they link to many of the strengths we’ve covered last time. In our next blog, I’ll share a bit more about some of the improvement opportunities that we see and coach staff and physicians to focus on as they work to improve the unexpected experience for their patients.